Describing mushroom anatomy is not always easy because there are so many unique types of mushrooms. Mushrooms are not a plant or an animal, but a species all their own that belongs to the fungi kingdom. We know they’re living, so they need to consume energy and reproduce, but how does their anatomy allow them to do it?

There’s much more to mushroom anatomy than what meets the eye – quite literally. The visible mushroom (fruiting body) that grows from the ground or tree shows only a small part of the fungis anatomy. Beneath the surface, they have minuscule hyphae that make up mycelial networks that can spread out for miles.

If you’re curious about the makeup of a mushroom and wonder what fungal parts contain health-supporting properties, this guide has you covered. Let’s take a look at the parts that make up a mushrooms anatomy, their functions, and health-supporting properties.

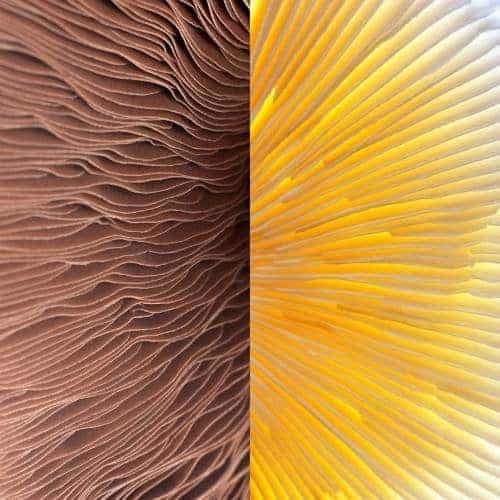

In mycology, a lamella ( pl. : lamellae), or gill, is a papery hymenophore rib under the cap of some mushroom species, most often agarics.

What is the Fruiting Body of a Fungus?

When you think of mushroom anatomy, the that comes to your mind is likely the mushroom itself, also known as the fruiting body, or the part that you eat. The reality is, that there is much more to mushroom anatomy beneath the surface. Just as an apple is to a tree, the mushroom is the fruit of these fungal organisms. The term “mushroom” is interchangeable with the term “fruiting body.” The mushroom is the “fruit” of the fungus.

For most common fungi, the mushroom, which can also be called a sporophore, is made up of a cap and stem. It only exists for a short period and its primary evolutionary function is to spread spores at the end of the mushroom’s life cycle. Some of these spores will go on to produce new mushrooms and restart the cycle (1,2).

Mushrooms have 4 primary structures:

Read on to learn about the functions, features, and variations of each of these structures.

Mushrooms can come in a vast variety of shapes, sizes, and colors. The common mushroom anatomy appearance that most are familiar with consists of a cap and stem.

The mushroom cap, also known as the pileus, is the structure on top of the mushroom that holds the gills or pores. They come in different shapes, sizes and textures. They can be smooth or covered with scales or teeth.

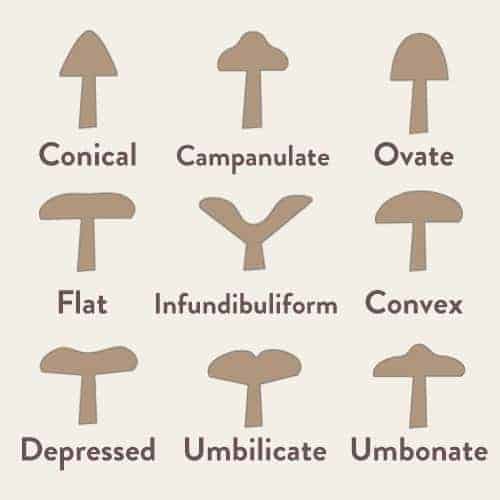

The shape of a mushroom cap is unique from species to species, which is helpful for identification. The familiar mushroom anatomy shape is somewhat spherical, like an umbrella. In the early stages of development, it can be evenly convex and then become more expanded as it matures. Some mushroom cap shapes include:

- Conical

- Campanulate (Bell-Shaped)

- Ovate

- Flat (plane)

- Infundibuliform (deeply depressed)

- Convex

- Depressed

- Umbilicate (small depression)

- Umbonate (knobbed)

But many mushrooms, like some of our favorite healthy mushrooms, have a look all their own. Take lions mane mushrooms for instance. They are a tooth fungus, meaning instead of a spherical dome cap, they have “teeth” or shaggy hair-like structures that hang down around the mushroom and produce spores.

Scales are part of a mushrooms anatomy that form hard-shelled protection for fungi. They often appear in various shapes and sizes, contributing to the unique physical appearance of mushrooms in the wild.

Scaly caps can be useful in the identification of mushrooms as numerous species have them. Scales typically appear on the cap, but can also be present on the stem. They often appear as the result of cracking as the cap expands during growth, but can also be seen when immature.

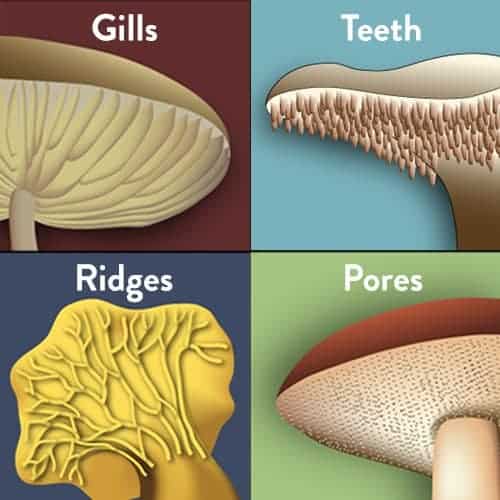

Beneath the cap of many common mushrooms, you’ll find either gills (also known as lamellae), pores, ridges, or teeth. These are the parts of a mushroom’s anatomy that produce and release spores (1).

These parts of a mushroom are important for identification because many species look similar based on the appearance of their cap. The underside of a mushroom is sometimes the only way to distinguish between edible mushrooms and poisonous ones.

The mushroom gill is a small, thin-walled structure that surrounds the stem of the mushroom. It has an opening on one side and is usually found in clusters around the stem of mushrooms.

The gills are composed of two layers, the lamellae that reach from the stem to the edge, and the lamellulae that are shorter gills that don’t reach the stem. Not all mushrooms possess lamellulae (3).

Gills can have many distinct characteristics that make the mushroom identifiable. Some include:

Gills can be attached to the stem or free, they can also have various forking or branching patterns.

Forking gills can be deceptive. For instance, chanterelle mushrooms have structures that look similar to forked gills but these are actually false gills. These structures often appear as smooth ridges underneath the cap. True gills, on the other hand, are separate parts of a mushroom that can be picked off. When it comes to identification, knowing the difference between true gills and false gills can be very helpful.

There are mushrooms whose undersides look deceptively similar to gills. As mentioned in the previous section, these false gills are actually ridges.

One test for figuring out whether a mushroom has ridges or gills is to try and detach the feature from the mushroom. If you can easily pull a segment of the underside’s feature away from the cap, you most likely have a gilled mushroom. If the feature seems to mold into the mushroom itself and cannot be easily detached from it, you most likely have ridges (false gills).

Chanterelle mushrooms and pig’s ears mushrooms (Gomphus clavatus) are examples that have forked ridges on the underside of the cap.

Other types of mushrooms have pores instead of gills. Like gills, pores produce spores, but they appear as small, sponge-like holes instead of thin blades.

The little holes lead to tubes inside the cap. As spores mature, they eventually fall from the tubes out of holes and into their environment. Similar to gills, these mushroom parts are helpful in indicating the species. Color, size, pattern, and quantity, are all pore traits that are useful in indicating the species.

Boletes and polypores are two common types of mushrooms that are known to have pores.

Porcini is a well-known edible mushroom that is a bolete. Although, not all boletes are as tasty as the porcini, or even safe to consume.

Polypores, on the other hand, are almost always found growing on rotting wood. Turkey tail is an example of a polypore. They are a type of healthy mushroom that grow flat off the sides of decaying wood and fan out as they mature. As they grow they develop rings of different shades of brown and white that make them resemble a turkey’s tail.

Like the turkey tail, other polypores are usually shelf-shaped and non-poisonous.

As we mentioned earlier, some mushrooms have developed some interesting traits to disperse their spores. Some of these traits include long, thin, shaggy growths that hang from the mushroom cap called teeth. The teeth of a mushroom can be a few millimeters to a few centimeters long.

These teeth, also known as spines, make it easier to narrow down the species of mushroom because they’re less frequent compared to gills or spores. The hedgehog mushroom is a common mushroom that has short teeth that hang from the underside of its cap. As noted before, lion’s mane mushrooms (also called bearded tooth mushrooms) also have teeth, but theirs grow from its stem where other mushrooms would have a cap.

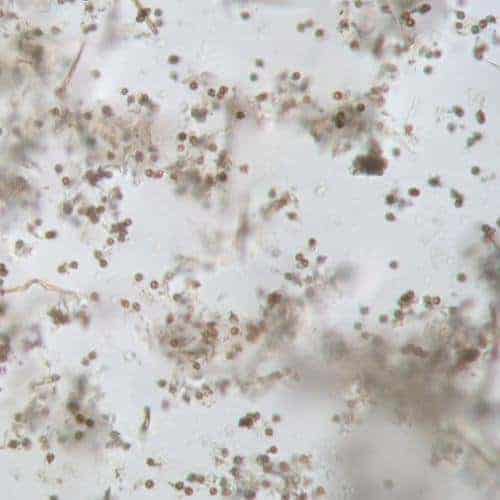

The microscopic reproductive cells that make it possible for fungi to replicate are called spores. Just like plants need seeds to reproduce, mushrooms need spores. If the visible mushroom is the “fruit”, the spore is the “seed”. Spores are found under the mushroom cap, within the gills or pores (1).

Spores are unique in that they are able to form into a new mushroom without needing to fuse into another reproductive cell. There are no male or female spores because mushrooms typically reproduce asexually. Although, they do have the ability to reproduce sexually when two compatible mycelia clumps fuse (2).

Mushrooms can release trillions of spores every day, but they don’t produce spores all the time. They will only create spores if conditions are ideal. Mushrooms need ample nutrients and water to produce spores and carry out their life cycle (2).

(Include interesting examples such as the Lycoperdon and stinkhorns adaptations, such as smell, slime etc. to encourage maximum spore dispersal. For example, the veiled lady’s “netting.”)

Mushrooms have developed many creative and fascinating methods for dispersing their spores. Some simply drop or eject their spores from their gills, pores, or teeth, and allow critters, water, or a light breeze to carry them off to their new destination. If they’re lucky, they’ll fall onto the fertile ground and restart the mushroom life cycle (4,5).

Some have evolved in interesting ways to encourage maximum spore dispersal. The Lycoperdon perlatum, also known as the common puffball, is one of them. They have one large pore at the top of their cap through which spores are released. When something bumps into them, like raindrops or small animals, a large number of spores are ejected in a smoke-like cloud (4,5). Fun fact: Lycoperdon translates to “wolf farts” in greek.

The stinkhorn is a mushroom that works with insects to disperse their spores. This mushroom has a very pungent smell that attracts flies, ants, and other bugs. It also secretes a sticky slime that contains their spores. So when insects crawl all over them, they inevitably get the slimy spores stuck to them, and they carry them off to a new destination (6).

Chaga is a fungi that grows on birch trees and has no spores. Instead, its spores develop underneath the trees bark and accumulates around the chaga conk as the tree dies. From there, the spores disperse into the air to find new trees to grow in.

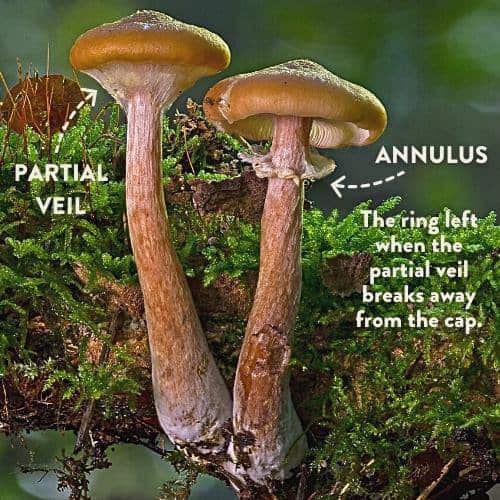

A mushroom stem is the stalk of a mushroom, it’s also sometimes referred to as the stipe. Its primary function is to support the cap and the spores it contains. This part of a mushroom is long, sturdy, and shaped like a cylinder. The stem usually has an annulus or vulva attached to it. These parts of a mushroom protect the spores during development (7).

When some mushrooms are in the early stages of growth, they develop a partial veil that surrounds and protects the underside of the cap. As the mushroom matures and expands, its partial veil breaks away from the cap and is left hanging around the stem. This hanging part is the annulus, or mushroom ring (7).

Other types of mushrooms also have a universal veil that encapsulates the entire mushroom during early development. As it matures, the universal veil breaks off. The pieces of the universal veil that remain attached to the bottom of the stem are the vulva (7).

Fragments of the universal veil often stick to the cap in patches, resembling warts. For instance, Amanita Muscaria’s white spots are fragments of its universal veil.

Usually, mushrooms with a universal veil also have a partial veil. Since both parts of a mushroom are present, they will have a vulva and an annulus.Watch this time-lapse to see the Amanita Muscaria (Fly Agaric) emerge from its universal veil and grow into a bright red mushroom. The remains of its veil form the vulva at the stem’s base.

Mycelium is an unseen but fascinating part of mushroom anatomy. They are made up of small networks of threads called hyphae. The primary function of mycelium is to collect nutrients and water.

Environmental conditions need to be just right in order for the mycelium to produce a mushroom. Some mycelium can live for hundreds, even thousands of years without producing a mushroom. All mushrooms come from mycelium, but not all mycelium will produce mushrooms (1,2).

Medicinal Parts of Mushrooms

Each part of a mushroom’s anatomy is equally important for supporting the life cycle of a fungus. But is each component equal when it comes to medicinal value? Let’s take a look.

Medicinal mushrooms such as reishi, lion’s mane, cordyceps, turkey tail, and chaga contain a variety of nutrients and compounds that can be beneficial in supporting your health. Most of their key medicinal benefits come from their polysaccharide content, particularly beta-glucans. Studies show that beta-glucans can help balance your body’s immune response, support healthy blood sugar levels, and balance energy levels (8,9).

Fungal Morphology: The Parts of a Mushroom

FAQ

What’s the bottom of a mushroom called?

What is the part of a mushroom found below ground called?

What are the different parts of a mushroom?

Which part of mushroom is not edible?

What is the top of a mushroom called?

The top of a mushroom is called the fruiting body. The mushroom cap and stem are typically the above ground parts of a mushroom that we see. What is the mushroom stalk?

What are reishi mushrooms?

The reishi mushroom is a fungus with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory properties and that contribute to cardiovascular and immune health. However, the evidence is still inconclusive about its benefits.

Which part of a fungus is called a mushroom?

Which is the part of the fungus we commonly refer to as a mushroom. The cap of the mushroom is the topmost part and gives the fungi its umbrella-like shape. It can be flat, conical or spherical and have a wide range of textures and colors. The caps’ color and texture don’t only vary by species.

What is the underside of a mushroom?

The underside of a mushroom can have one of 4 types of structures: gills, teeth, ridges, or pores. Source. The mushroom gill is a small, thin-walled structure that surrounds the stem of the mushroom. It has an opening on one side and is usually found in clusters around the stem of mushrooms.